By Nazia Tasnim, S. M. Rafiquzzman, and M. Gulam Hussain

Overall editing and formatting by Laura Skrobe and Alaina Dismukes

Bangladesh has a large coastal belt at the Bay of Bengal that provides food for millions of people, primarily through coastal fishing and aquaculture. Shrimp is the most valuable farming product; however, disease outbreaks, severe infestations, and environmental degradation have caused a severe decline in abundance. Mud crab (Scylla serrata) is an incidental product that provides a marginal return to farmers to help alleviate this loss (Rahman, 2017).

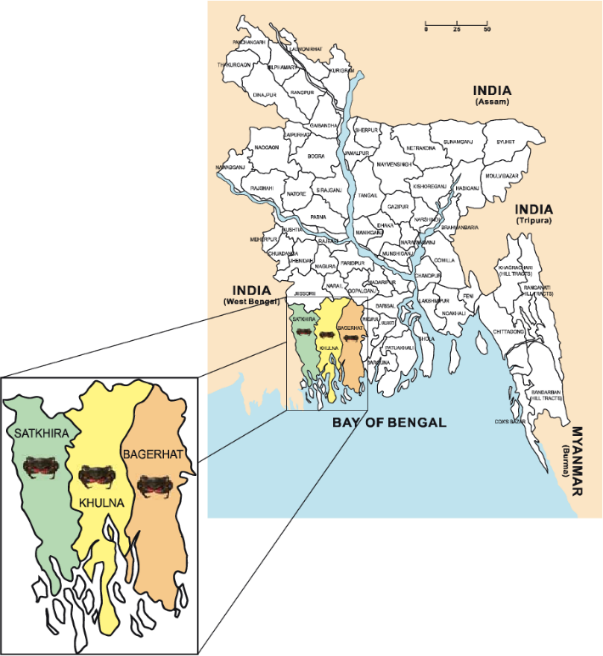

In recent years, many shrimp farmers and producers have left conventional shrimp farming and switched to crab fattening and farming (Figure 1). Mud crab aquaculture employs over 300,000 people, either directly or indirectly. Crab farming directly contributes to increased income for women farmers and gross domestic product (GDP) for Bangladesh. Earning money for the family increases women’s confidence, integrity, and participation in decision-making within their households in the southwest region of Bangladesh.

1. Crab Farming in Bangladesh

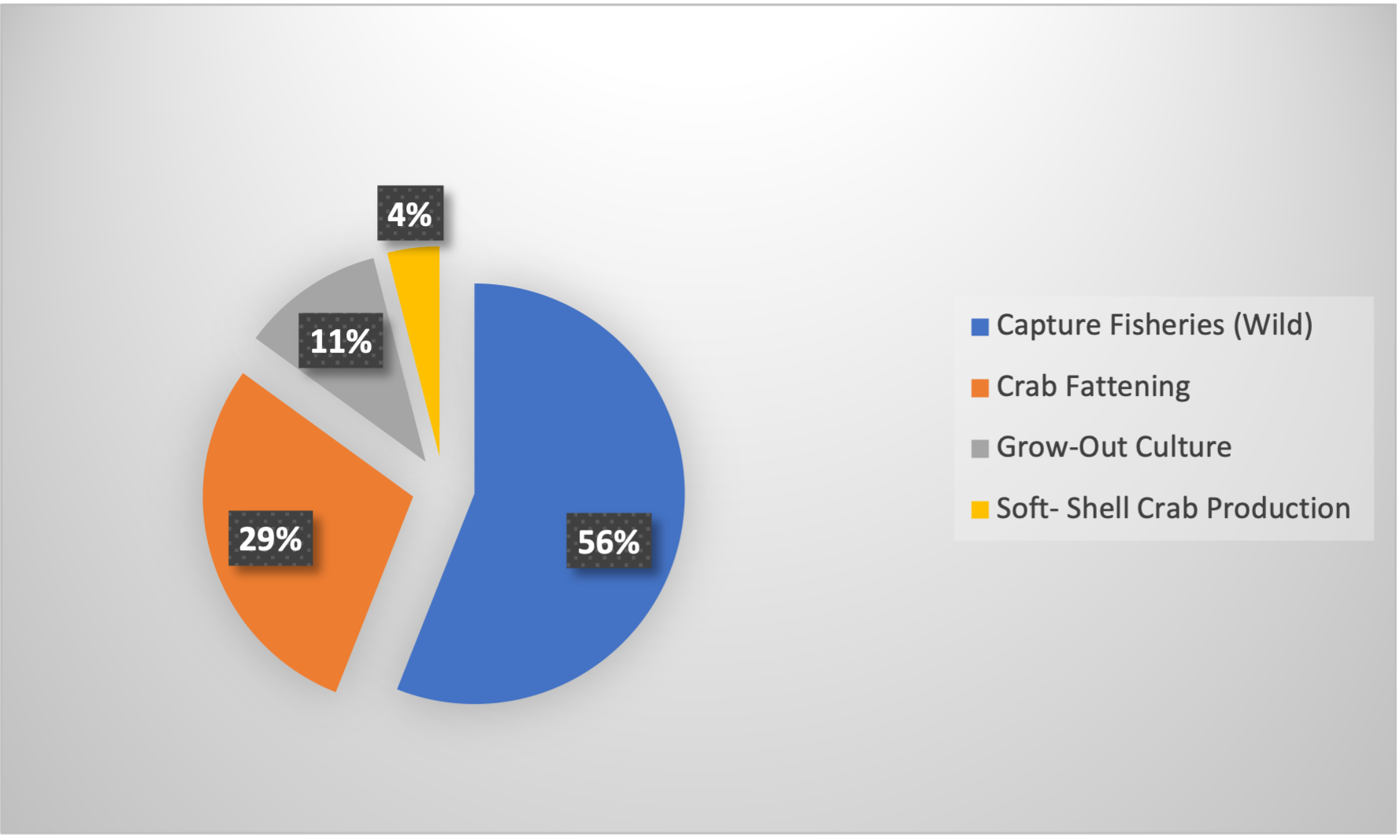

Crabs are the second most exported crustacean product from Bangladesh. The major species for export is the mud crab, which was first exported in 1977. As the demand for mud crab in the international markets has increased, the number of crab gatherers and farmers has also significantly increased. The cultural techniques of this crab are as follows:

1.1 Crab fattening

Fattening of postmoult as well as immature water crabs are conducted in the ponds to produce egg crabs (females with ripe ovaries) and hard-shelled meat crabs (preferably a male with a hard body and large intact claws). Gravid females (egg crabs) are the most valuable hard-shelled crabs in Asian markets and are sold for as much as US $14 per kg. In Bangladesh, crab fattening is now very popular in Paikgachha, Mongla, Satkhira, Kaliganj, and the Munshiganj areas of the greater Khulna region. Approximately 38% of coastal shrimp farms had been wholly converted into crab-fattening farms from penaeid shrimp culture.

1.2 Soft-shell crab production

The brackish water and marine coastlines of Bangladesh are well suited for soft-shell crab farming. In Bangladesh, soft-shell crab farming started in 2010 and spread to the southwest part of the country by 2015. In Satkhira District, there are approximately 39 soft-shell crab farms; the majority are owned by non-local, affluent investors. Soft-shell crab markets are not open to all farms, and only experienced, larger-scale farms with export licenses are viewed as acceptable by buyers in the international export markets. Bangladesh’s export of soft-shell crabs is relatively new, and no data is available on their value or quantity.

2. Involvement of Women in Crab Farming

The crab sector has provided a variety of economic possibilities for the coastal poor and marginalized women who were working as non-waged laborers. Women are involved in crab farming in a variety of ways, including building enclosures, traps, baskets, and fishing tackle, as well as gathering and selling trash fish, snails, and other low-value species from open freshwater and saltwater sources (Figure 3). In addition, women participate in selling nets, medications, lime, thread, and crab foods. Many women are employed by crab depot owners and suppliers to purchase, check, grade, and package crabs.

In coastal areas, commercial soft-shell crab farms create significant employment opportunities, especially for women. In southern coastal Bangladesh, 74% of crab fatteners are women and around 20% of crab seed harvesters are women. Female employees are from impoverished households, and a majority are divorced, widowed, or separated from their families.

Women’s participation in crab aquaculture frees up males to work outside, lowering family vulnerability to poverty. Women, their husbands, and other males travel to the nearby mangrove forest during high tide in the morning and return during low tide to sell collected crabs to local depots, earning 250-300 Bangladesh taka (BDT) daily.

Many women purchase rejected crabs (damaged, underweight with developed gonad, immature developed gonad) from depots of secondary markets and sell them to domestic markets. Some women purchase various trash-fish or other low-value fish from markets, collectors, fish farmers, and gher (i.e., enclosures) owners, and then chop them into small pieces to sell to fatteners as crab feed.

3. Women’s Empowerment and Socio-economic Mobilization

Crab farming in Bangladesh serves as a hedge for women against poverty and provides access to the market, food, health services, and education. This sector advocates for long-term and significant changes in women's lives, addressing gender disparities in resource access and control as well as decision-making. Furthermore, by involving all coastal residents, the mud crab industry is promoting social relations. It provides a mirthful environment for vulnerable and poverty-stricken women in coastal areas. Most significantly, the crab fishery provides alternative livelihoods for vulnerable communities in the coastal region of Bangladesh, allowing them to adapt to changing climate conditions.

4. Earning and Fetching Price Before and After COVID-19

Before the Covid-19 pandemic, the Bangladesh government earned considerable foreign currency through crab exports to international markets, mostly to China (92%), Taiwan, Malaysia, Singapore, North America, and European countries. Foreign currency earnings increased every year, US $6.7 million in 2010-2011 and US $21.1 million in 2013-2014 (DoF 2015). The sector was growing toward a potential industry for the marginalized coastal communities and the country’s economy.

At the start of the Covid-19 outbreak, China banned crab imports, and crab exports suddenly dropped. The Chinese import market remained closed even during their mid-Autumn festival in October when crabs are traditionally eaten as part of the celebrations. Additionally, China stopped accepting crabs from Bangladesh due to the lack of required laboratory tests and the use of false certificates by some exporters. Subsequently, crab prices took a nosedive after the Chinese market was shut down.

As demand crashed, the price of crabs in the domestic market fell by two-thirds. Bangladesh sold crabs worth $35 million in the fiscal year 2019-2020, but earnings dropped to $12 million in the fiscal year 2021, according to the Export Promotion Bureau. Local demand was also very low in the country. For cultural reasons, eating crab is not popular in Bangladesh since it is a Muslim-majority country. Higher caste Hindus also avoid shellfish.

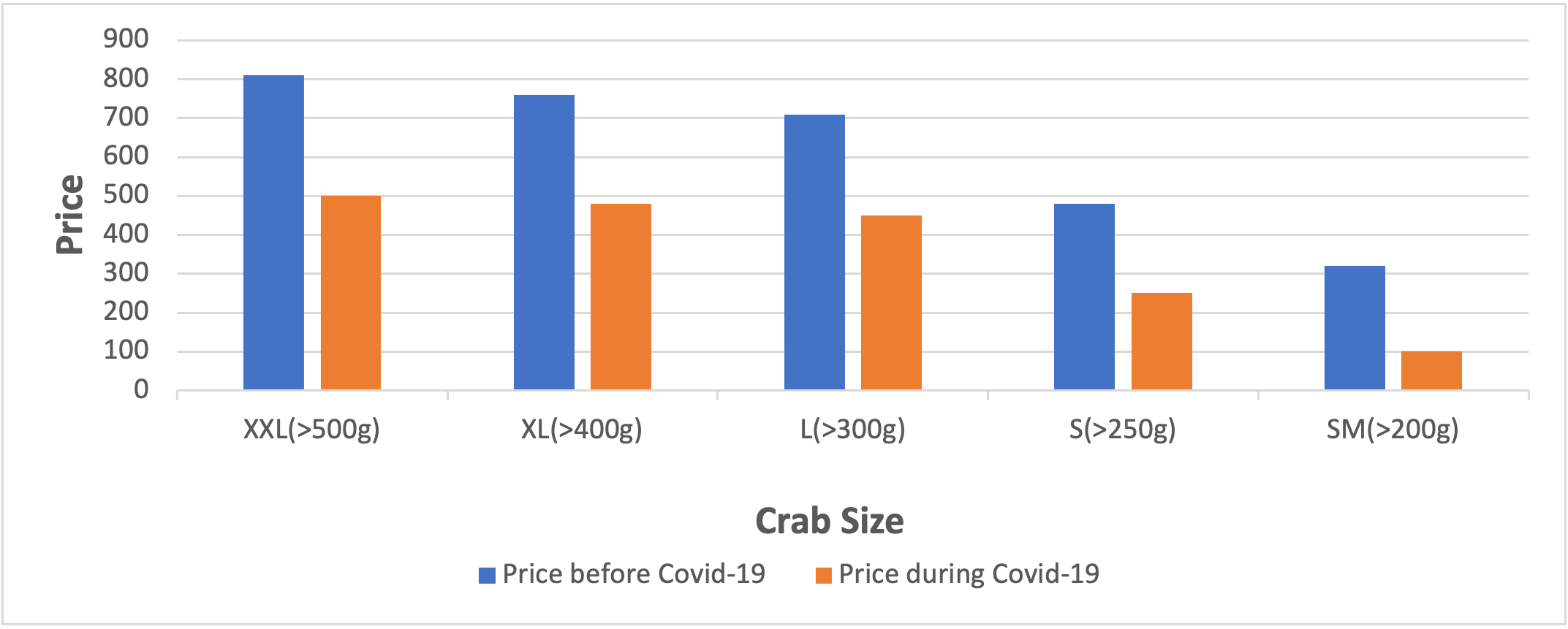

According to some local men and women crab growers in Shyamnagar, Satkhira, their business took a bad hit due to the pandemic. They stated they did not realize how terrible the Covid-19 disruption would be, but business came to a standstill within weeks after the closing of the borders, which resulted in severe financial losses. Some of them even left the trade altogether. The following is the statistical report gained by visiting some crab farms in Satkhira (Figure 5).

Before the pandemic, the price was around BDT 800 per kg. for crabs weighing 500 grams each, and after the coronavirus outbreak, it dropped to around BDT 500. In addition, crab collection and farming got disrupted.

5. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Women in Crab Fattening Farms

As crab farming in Bangladesh is totally export-based, female crab farmers in Bangladesh struggled to feed their families after exports to China collapsed due to the Covid-19 pandemic. According to BLCFEA, China alone accounts for 90% of crab exports. Although the export of crabs resumed after the lockdown ended on April 26, 2020, the crab growers are still struggling because they have already suffered significant losses

Most of the female crab farmers who are dependent on bank loans for farming, counted heavy losses due to the sudden suspension of crab exports since crabs become saleable in three months but die if not sold in time. Although some of them were able to sell crab to local markets, lack of demand has seen the price drop by 80%, from BDT 1,000 per kg. to BDT 200. With no sign of recuperation of losses in sight and the re-start of crab exports on a meager scale, female crab farmers have been left struggling to survive amid the COVID-19 pandemic. As the sale of crabs is regarded as the only source of earning for their livelihoods, the female crab farmers have been plagued with various problems. Though the export reopened at the end of April 2020, they were still not able to supply the crabs as per their expected level as they were still battling to collect all the money they lost.

Exporters suffered losses amounting to over BDT 5 billion during the first four months of the pandemic. Crabs died in different farms as the export remained halted, and around 200 farmers in the Bagerhat District were affected. At present, the export certificate is issued only after the products undergo 12 or 13 tests at three fisheries department laboratories in Savar, Chattogram, and Khulna, which creates more problems for the small-scale female crab farmers, and they have to sell crab either to large farms or locally at a lower price.

6. Initiatives Taken by the Government

The certificates required by China have been arranged in coordination with the Ministry of Fisheries and Livestock; therefore, there are no more obstacles to the export of crabs. Any company can export crabs to China in compliance with the new rules, so those who ceased crab farming can resume production.

To further boost the industry since most young crabs are caught in the wild and catches have been falling with growing demand, women in coastal communities are receiving special training as well as 100 crab cages and a free setup for crab farming. Also, the government fisheries department is now trying to establish crab hatcheries in the country and discouraging capturing wild, young crabs from coastal waters.

Recommendation:

While fish farming is traditionally perceived to be a full-time occupation for men, the involvement of women is also significant. Women in Bangladesh face substantial challenges to engage in and benefit equitably from crab farming. At play are a combination of factors, including limited access to and control over assets and resources, constraining gender norms, time and labor burdens of unpaid work, and barriers to sustaining entrepreneurship. This results in women having fewer opportunities and receiving smaller returns than men, including lower-income and being left in positions of poverty. If women are given equal access to critical resources, such as land, and are part of the planning, design, and management process, the efficiency, profitability, and sustainability of crab production will be enhanced, and their socioeconomic and political status will be upgraded.

References

Abdullah-Al Mamun, J. S. (2021). Qualitative assessment of COVID-19 impacts on aquatic food value chains in Bangladesh (Round 2). Penang, Malaysia: CGIAR Research Program on Fish Agri-Food Systems. Program Report. Retrieved from https://digitalarchive.worldfishcenter.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.1234….

Ahmed, A. T. (n.d.). Banglapedia. Retrieved from https://en.banglapedia.org/index.php/Crab.

Aliza Sultana, R. S. (February 2019). Value chain analysis of mud Crab (Scylla spp.) in southwest region of Bangladesh.

As floods rise in Bangladesh, crab farming helps families tread water. (2018, March 23). Retrieved from Flood Resilience Portal: https://floodresilience.net/blogs/as-floods-rise-in-bangladesh-crab-far….

Atihk, F. (2021, July 31). bdnews24. Retrieved from bdnews24.com: https://bdnews24.com/business/2021/07/31/bangladesh-resumes-crab-export….

Colin Shelley, A. L. (2011). Mud crab aquaculture: A practical manual. Rome: FAO.

FAO.org. (2016). Retrieved from Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: https://www.fao.org/3/i6623e/i6623e.pdf.

Hodal, K. (2020, September 11). Retrieved from The Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/sep/11/blow-for-ban….

Islam, M. S. (n.d.). Status of mud crab aquaculture in Bangladesh. Proceedings of the International Seminar-Workshop on Mud Crab Aquaculture and Fisheries Management, 10-12 April 2013, Tamil Nadu, India, Tamil Nadu, India: Rajiv Gandhi Centre for Aquaculture (MPEDA)., (pp. 1-6).

M. Kamruzzaman, S. D. (2020, February 12). Retrieved from UNB- United News of Bangladesh: https://unb.com.bd/category/Special/crab-farmers-exporters-feel-the-pin….

M. Mojibar Rahman, S. M. (2020). Assessment of mud crab fattening and culture practices in coastal Bangladesh: understanding the current technologies and development perspectives. AACL Bioflux, 13(2). Retrieved from http://www.bioflux.com.ro/docs/2020.582-596.pdf.

Md Mojibar Rahman, M. A. (June 2017). Mud crab aquaculture and fisheries in coastal Bangladesh. World Aquaculture, 47-52.

Md. Hojibar Rahman, S. M. (2018, September). Soft-Shell Crab Farming in Bangladesh: Prospects, Challenges and Sustainability. (J. Hargreaves, Ed.) World Aquaculture, 49(3), p. 43.

Prothom Alo. (2020, June 18). Retrieved from Prothom Alo: https://en.prothomalo.com/business/local/bangladesh-crab-farmers-strugg….

Rahman, Md & Islam, M Ashraful & Haque, Shahroz & Wahab, Md. (2017). Mud crab aquaculture and fisheries in coastal Bangladesh. World Aquaculture. 48. 47-52.

S. Halim, M. A. (n.d.). Women IN fisheries IN BANGLADESH: level of involvement and scope for enhancement. Global Symposium on Gender and Fisheries (pp. 1-168). WorldFish Center.

Savage, S. (2021, February 12). Retrieved from The Telegraph: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/global-health/climate-and-people/brink-dest….

Singh, G. (2016, September 29). Retrieved from Down To Earth: https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/economy/crab-fattening-a-business-o….

(n.d.). VSO. Retrieved from VSO: Voluntary Service Overseas: https://www.vso.ie/fighting-poverty/where-we-fight-poverty/bangladesh/c….

About the Authors

Nazia Tasnim is currently an assistant research fellow at the Fisheries Biology and Aquatic Environment Lab, Faculty of Fisheries, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Agricultural University, Gazipur, Bangladesh.

S. M. Rafiquzzman is a professor at the Department of Fisheries Biology and Aquatic Environment, Faculty of Fisheries, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Agricultural University, Gazipur, Bangladesh.

M. Gulam Hussain is the Asia regional coordinator at the Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Fish and the former director general at Bangladesh Fisheries Research Institute (BFRI).

Published February 2, 2023